Bootloaders and ARM Cortex-M microcontrollers: Booting the target application

Contents

In a previous blog we discussed the role of the NVIC in ARM Cortex-M microcontrollers. This peripheral will play a central role in booting our target application. First of all, we need to discuss the boot process in an ARM Cortex-M microcontroller.

Boot process

- After Power On Reset the microcontroller assumes the NVIC table is located at address 0x00000000.

- The processor fetches the first two words in the NVIC table, corresponding to the top of the stack and the reset vector.

- It sets the MSP (Main stack pointer) to the top of the stack.

- It jumps to the address indicated by the reset vector.

- Application program execution begins.

In the case of our bootloader, the processor will be loading the top of the stack and the reset vector of our bootloader and then start executing it. Then, we the bootloader decides if it can boot an application already present at flash memory or if it needs to load an application using the loader. No matter which is chosen, it will eventually have to boot the target application.

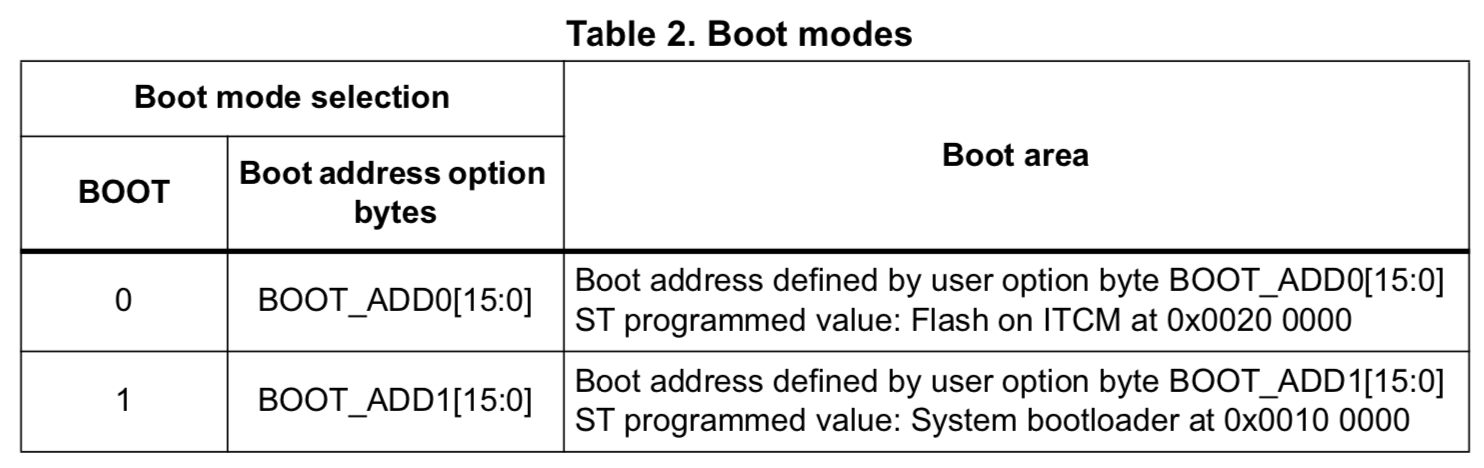

Looking at the regular reset process we can see that there is a big assumption the processor makes. It assumes that the NVIC table is located at address 0x00000000. This is why many vendors actually provide boot pins to alias the first section of memory to other memory sections or devices. This is used also for embedding vendor-provided bootloaders into an OTP memory and such. For example, an STM32F7 processor uses the following boot pin configuration:

Some microcontrollers will even provide you with methods to override these boot addresses, but we will assume that is not an option for us (to make our bootloader more generic).

So in order to boot the target application we have to replicate the boot process the processor does at the hardware level.

Booting the target application

Now that we know the requirements to boot the target application, we have all the tools we need to develop our own boot code. The easiest way is to:

- Obtain the NVIC relocation offset for the target application. This information is dependent on the target application itself, but we can simply provide this information to the bootloader when we load the ELF file through a bootloader application for a host computer. We will use the convention that the NVIC table is located in an ELF section called

.isr_vector. - Set the NVIC relocation offset so that after booting the target application all interrupts and exceptions will actually call the target application code. This is done via the

VTOR(Vector table offset register). - Before setting the NVIC relocation offset though, we have to make sure that we disabled all peripherals and interrupts. Otherwise, if we are using the UART1 and the target application doesn’t we risk entering the default ISR handler of the target application. This handler is typically an infinite loop.

- Now we are 100% ready to boot the target application. We simply set the MSP to the first word of the target NVIC table.

- Then we jump to the Reset vector of the target application code (which we know is the second word in the target application NVIC table).

This is what we do in the following lines of code:

| |

The boot method is receiving the address at which the NVIC table is located. It disables all peripherals and relocates the NVIC table. Finally, it loads into the SP register (which in our application is the MSP since we don’t use the PSP) and then loads the program counter (PC) with the address located at the second word of the target application NVIC table.

There is a good reason why the last two instructions are written in assembly. In C/C++ there is no way for us to access the stack pointer and write it as a register. The same goes for the program counter. You could, in theory, declare a function pointer to a function that doesn’t take any arguments and doesn’t return anything and make it point to the reset vector and then call the function. Since the function doesn’t take any arguments it should not mess with the stack pointer. However, it is more explicit and less confusing to do this small bit in assembler.

A note about the top of the stack

Notice how in the code I didn’t actually use the target application NVIC table to obtain the top of the stack. Instead, I am using __estack_, a constant defined by the linker at compile time (as given by my linker script config).

The reason for doing this is simply that there is no need to lookup this value in the target application. The top of the stack doesn’t change (or shouldn’t) between the bootloader and the application, so we might as well use the bootloader value.

However, there might be some cases where you’d want to customize this for the target application. Think about reserving memory outside the C/C++ memory layout for another use. Since this isn’t a common usecase, I decided to ignore it and go with the value from the bootloader.

Tips for writing the target application

It’s important to remember that our target application will not be located in the common memory addresses that our IDE or example code might supply us with. This means that we need to make sure that the region of memory reserved for the bootloader is not written and will not be written in runtime.

So, in the linker script for the target application we must declare the Flash memory starting from the second block of Flash memory instead of the first.

| |

Another important detail is that many vendors use the startup code to set the the NVIC Table Offset to the start of the Flash or the start of RAM (depending on the configuration for the project). If you see that after booting the application an ISR located in the bootloader is getting called, that’s most likely the reason. You need to make sure that the VTOR register is not modified after boot. Otherwise, your application will not behave as intended.

Author Javier Alvarez

LastMod 2019-10-12