Cross-compiling for embedded devices

Contents

Developing code for embedded devices is somewhat different from code for mainstream computers. One of these differences is the development environment.

Most of the target microcontrollers or microprocessors won’t usually be suited for local development. Imagine trying to build your code on the target when the target is a simple 8-bit Microcontroller. First of all you would need a compiler for the target architecture on the target device and it would probably be extra slow and inconvenient. That is the reason behind cross-compilers (provided that the uC has enough power and memory to perform the compilation process).

Cross-compilers are run on mainstream computers, whilst they generate code for the target Microcontroller (which will most likely have a different architecture). This is crucial when we are developing code for target processors that don’t support a mainstream operating system such as GNU/Linux.

Having a cross-compiler is useful even when the target device supports GNU/Linux. Think of the Raspberry Pi. It could be, after all, a small personal computer. You could compile code on the device. However, there are still reasons for using cross-compilers with embedded Linux devices, being the most common speed and convenience.

Many times we work on embedded devices for which we don’t have yet the target hardware available. In order to keep the schedule and being able to meet tight deadlines we are better off starting a dual-target project until the target hardware is available. Establishing a build environment on a mainstream computer is then paramount. You could even start testing some of the hardware dependent features on emulators such as QEMU, while most of the application code could be testable and subject to Test Driven Development (We will talk about this in the future, since it is not only applicable to embedded devices, but an integral part of developing good quality code for any type of device) on the local and target architectures.

How do cross-compilers work?

Well, they work just like any other compiler. The main difference is that the generated binaries and elf files cannot be run on the local architecture. For an example about a compiler we will examine the GCC toolchain:

GCC is an acronym for GNU Compiler Collection. It is not just a compiler, but also some other assorted tools that let you manipulate executable files and generate binaries in multiple formats. The C compiler in GCC is also called gcc (GNU C Compiler), whilst the C++ compiler is a binary named g++.

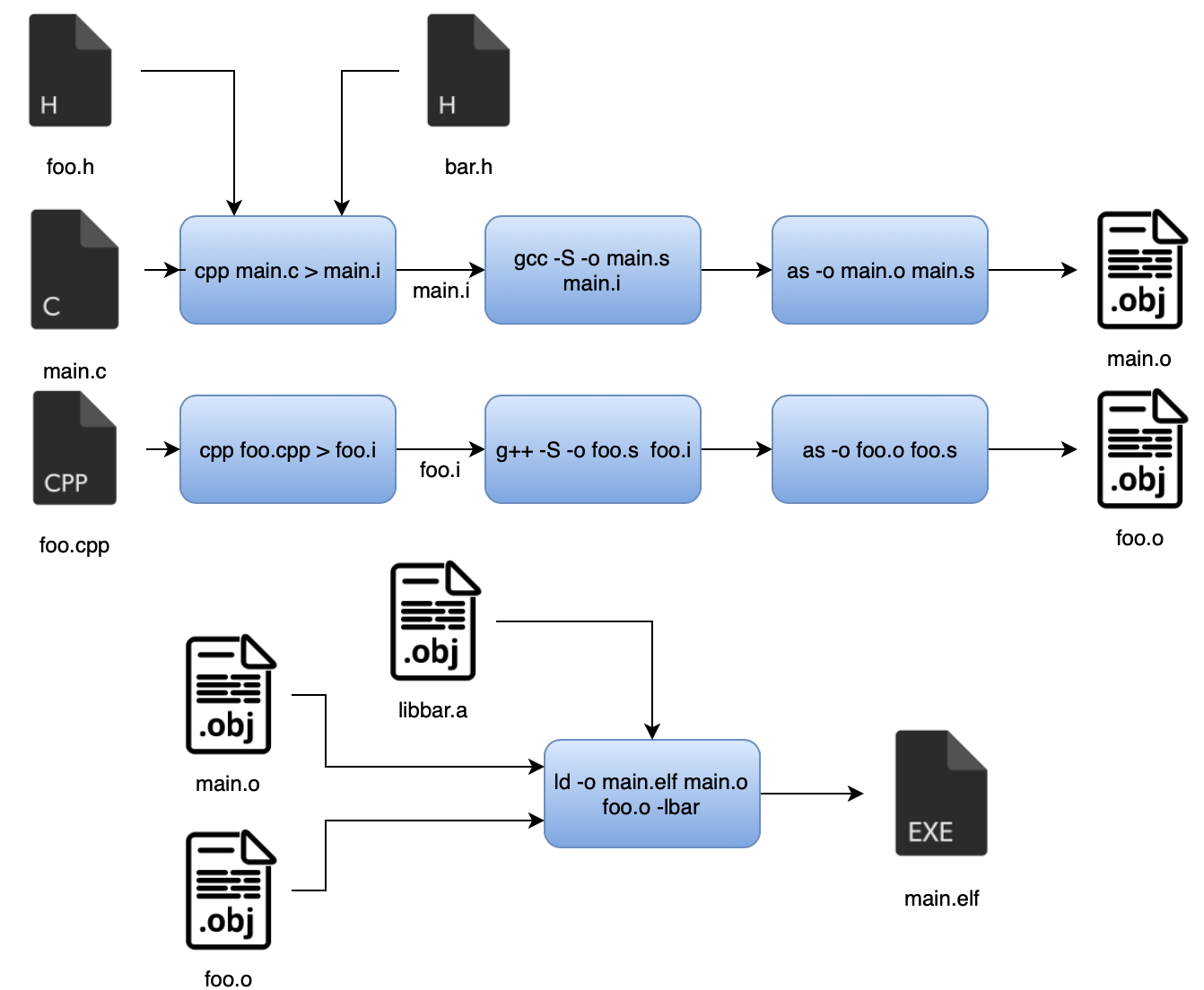

The job of the compiler is to take source code and transform it into some object code that is able to run on the target platform. This is done in a few separate steps:

- Preprocessing:

- The first step is running the C Preprocessor on each of the source files. This will replace all preprocessor directives such as #define and #include, creating a final file that can be parsed by the compiler itself. It substitutes all define directives and includes all header files in the source file, as well as handling some compile time conditional statements such as #ifdef.

- GCC can run this phase using the cpp command.

- Compilation:

- This stage takes care of translating all the source code to the assembly language required for the target processor. The compiler usually translates the source code first into an intermediate representation that can be interpreted by the optimizer and with which it can decide to make optimizations on the code to reduce the size of it and increase performance. Later, this intermediate representation is translated into the ASM language used for the target language. Function names and variable names are translated into symbols that are exported whenever it is necessary. Unresolved symbols will be taken care of later in the build process.

- GCC can run this phase using the gcc -S or g++ -S commands

- Assembly:

- Once the code for each source file has been transformed into ASM files, the assembler can run and convert each of the instructions into machine code or object code that can be run directly on the target. In addition to the machine code, the object file also includes information about the symbols required and contained within the code.

- GCC uses the as command to assemble the ASM sources.

- Linkage:

- The last step in this process is the running the linker. This step takes care of resolving missing symbols and can perform optimizations such as removing unused code and data. It basically merges all object files into a single executable. The linker can also link other code contained in libraries (static or shared).

The build process can be summarized in the following image:

Building a cross-compiler toolchain

Now, let’s say that we need to work on a new device with the ARMv7m architecture and it will run on bare metal or some RTOS that is compiled with the application itself. We will need a cross-compiler toolchain to work on this device. Since ARMv7m is a pretty common architecture nowadays in the microcontroller world and it is very well supported, we can find a prebuilt GCC toolchain for all major OS’s here.

However this might not be the case for all embedded devices. It is a very painful process to build the whole toolchain from the sources. Not only that, but you will also need some support libraries (given that the target architecture is not the same as your development environment we can’t use the same libraries). These include libc, libc++, libm, etc. In the case of the prebuilt toolchain in the above paragraph, the library included in the toolchain is newlib-nano, a lightweight version of the C standard library aimed for better performance on small embedded devices that don’t require the support level of mainstream GNU/Linux environments.

Luckily there is an open source tool with which the toolchain creation process is greatly simplified. croostool-NG is an open source toolchain generator that can be configured using common tools such as menuconfig. I won’t be describing the whole installation and build process for a new toolchain, however, I will comment on the benefits of using this tool to build your cross-compiler toolchain.

There are similar projects that allow you to get build your own toolchain such as buildroot. However, buildroot is not only a toolchain generator, but it can also generate root file systems for Embedded Linux Devices with custom needs. It can even build the kernel and the bootloader. However, I still feel that crosstool-NG is a better solution for those projects where you will not use Embedded Linux, since buildroot is overkill and less specialized.

Author Javier Alvarez

LastMod 2018-12-29